Avogadro's law (sometimes referred to as Avogadro's hypothesis or Avogadro's principle) or Avogadro-Ampère's hypothesis is an experimental gas law relating the volume of a gas to the amount of substance of gas present.[1] The law is a specific case of the ideal gas law. A modern statement is:

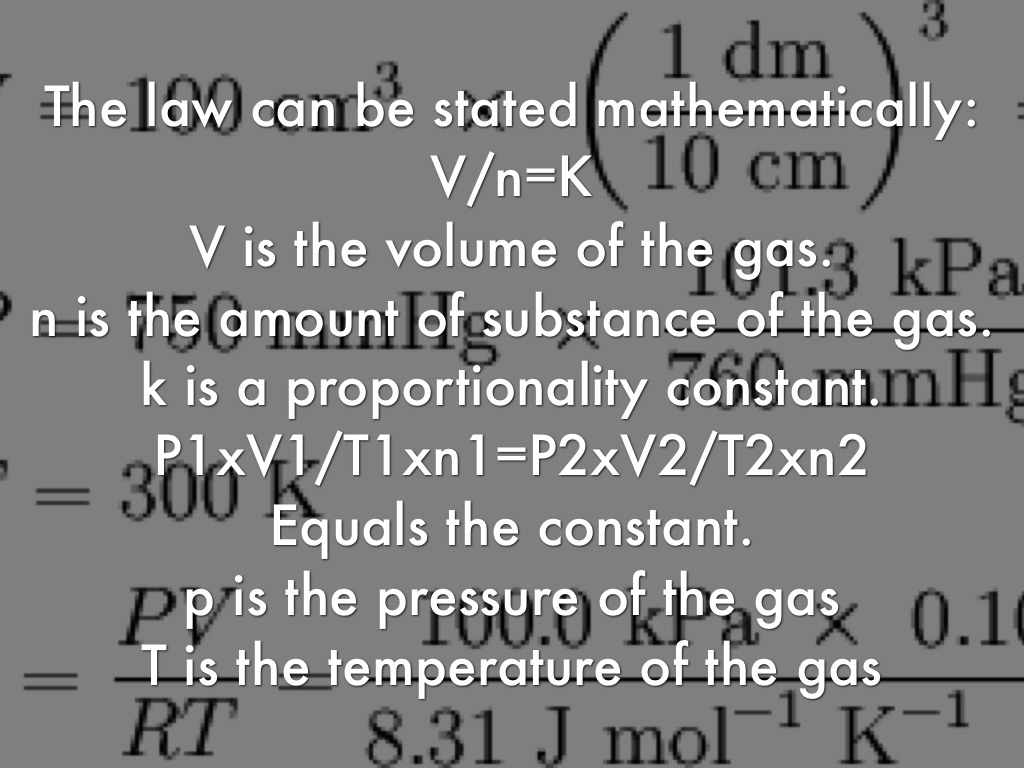

Formula: The Avogadro's law can be expressed through the next mathematical equation: V = k. Where V is the gas volume, n is the number of gas' moles and k is a constant, which is defined as RT/P, where R is a constant called the constant of the gases (8.314 kg m2 s-2 K-1 mol-1), T is the temperature in Kelvin and P is the pressure. Examples of Avogadro’s law in Real Life Applications As you blow up a football, you are forcing more gas molecules into it. The more molecules, the greater the volume. Quiz: Avogadro's Law Previous Avogadros Law. Next Ideal Gas Equation. Discovery and Similarity Quiz: Discovery and Similarity Atomic Masses.

Avogadro's law states that 'equal volumes of all gases, at the same temperature and pressure, have the same number of molecules.'[1]

For a given mass of an ideal gas, the volume and amount (moles) of the gas are directly proportional if the temperature and pressure are constant.

The law is named after Amedeo Avogadro who, in 1812,[2][3] hypothesized that two given samples of an ideal gas, of the same volume and at the same temperature and pressure, contain the same number of molecules. As an example, equal volumes of gaseous hydrogen and nitrogen contain the same number of atoms when they are at the same temperature and pressure, and observe ideal gas behavior. In practice, real gases show small deviations from the ideal behavior and the law holds only approximately, but is still a useful approximation for scientists.

Mathematical definition[edit]

The law can be written as:

or

where

- V is the volume of the gas;

- n is the amount of substance of the gas (measured in moles);

- k is a constant for a given temperature and pressure.

This law describes how, under the same condition of temperature and pressure, equal volumes of all gases contain the same number of molecules. For comparing the same substance under two different sets of conditions, the law can be usefully expressed as follows:

The equation shows that, as the number of moles of gas increases, the volume of the gas also increases in proportion. Similarly, if the number of moles of gas is decreased, then the volume also decreases. Thus, the number of molecules or atoms in a specific volume of ideal gas is independent of their size or the molar mass of the gas.

Derivation from the ideal gas law[edit]

The derivation of Avogadro's law follows directly from the ideal gas law, i.e.

- ,

where R is the gas constant, T is the Kelvin temperature, and P is the pressure (in pascals).

Solving for V/n, we thus obtain

- .

Compare that to

which is a constant for a fixed pressure and a fixed temperature.

An equivalent formulation of the ideal gas law can be written using Boltzmann constantkB, as

- ,

where N is the number of particles in the gas, and the ratio of R over kB is equal to the Avogadro constant.

In this form, for V/N is a constant, we have

- .

If T and P are taken at standard conditions for temperature and pressure (STP), then k′ = 1/n0, where n0 is the Loschmidt constant.

Historical account and influence[edit]

Avogadro's hypothesis (as it was known originally) was formulated in the same spirit of earlier empirical gas laws like Boyle's law (1662), Charles's law (1787) and Gay-Lussac's law (1808). The hypothesis was first published by Amadeo Avogadro in 1811,[4] and it reconciled Dalton atomic theory with the 'incompatible' idea of Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac that some gases were composite of different fundamental substances (molecules) in integer proportions.[5] In 1814, independently from Avogadro, André-Marie Ampère published the same law with similar conclusions.[6] As Ampère was more well known in France, the hypothesis was usually referred there as Ampère's hypothesis,[note 1] and later also as Avogadro–Ampère hypothesis[note 2] or even Ampère–Avogadro hypothesis.[7]

Experimental studies carried out by Charles Frédéric Gerhardt and Auguste Laurent on organic chemistry demonstrated that Avogadro's law explained why the same quantities of molecules in a gas have the same volume. Nevertheless, related experiments with some inorganic substances showed seeming exceptions to the law. This apparent contradiction was finally resolved by Stanislao Cannizzaro, as announced at Karlsruhe Congress in 1860, four years after Avogadro's death. He explained that these exceptions were due to molecular dissociations at certain temperatures, and that Avogadro's law determined not only molecular masses, but atomic masses as well.

Ideal gas law[edit]

Boyle, Charles and Gay-Lussac laws, together with Avogadro's law, were combined by Émile Clapeyron in 1834,[8] giving rise to the ideal gas law. At the end of the 19th century, later developments from scientists like August Krönig, Rudolf Clausius, James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann, gave rise to the kinetic theory of gases, a microscopic theory from which the ideal gas law can be derived as an statistical result from the movement of atoms/molecules in a gas.

Avogadro constant[edit]

Avogadro's law provides a way to calculate the quantity of gas in a receptacle. Thanks to this discovery, Johann Josef Loschmidt, in 1865, was able for the first time to estimate the size of a molecule.[9] His calculation gave rise to the concept of the Loschmidt constant, a ratio between macroscopic and atomic quantities. In 1910, Millikan'soil drop experiment determined the charge of the electron; using it with the Faraday constant (derived by Michael Faraday in 1834), one is able to determine the number of particles in a mole of substance. At the same time, precision experiments by Jean Baptiste Perrin led to the definition of Avogadro's number as the number of molecules in one gram-molecule of oxygen. Perrin named the number to honor Avogadro for his discovery of the namesake law. Later standardization of the International System of Units led to the modern definition of the Avogadro constant.

Molar volume[edit]

Taking STP to be 101.325 kPa and 273.15 K, we can find the volume of one mole of gas:

For 101.325 kPa and 273.15 K, the molar volume of an ideal gas is 22.4127 dm3⋅mol−1.

See also[edit]

- Boyle's law – Relationship between pressure and volume in a gas at constant temperature

- Charles's law – Relationship between volume and temperature of a gas at constant pressure

- Gay-Lussac's law – Relationship between pressure and temperature of a gas at constant volume.

- Ideal gas – Mathematical model which approximates the behavior of real gases

Notes[edit]

- ^First used by Jean-Baptiste Dumas in 1826.

- ^First used by Stanislao Cannizzaro in 1858.

References[edit]

- ^ abEditors of the Encyclopædia Britannica. 'Avogadro's law'. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 February 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^Avogadro, Amedeo (1810). 'Essai d'une manière de déterminer les masses relatives des molécules élémentaires des corps, et les proportions selon lesquelles elles entrent dans ces combinaisons'. Journal de Physique. 73: 58–76.English translation

- ^'Avogadro's law'. Merriam-Webster Medical Dictionary. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^Avogadro, Amadeo (July 1811). 'Essai d'une maniere de determiner les masses relatives des molecules elementaires des corps, et les proportions selon lesquelles elles entrent dans ces combinaisons'. Journal de Physique, de Chimie, et d'Histoire Naturelle (in French). 73: 58–76.

- ^Rovnyak, David. 'Avogadro's Hypothesis'. Science World Wolfram. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^Ampère, André-Marie (1814). 'Lettre de M. Ampère à M. le comte Berthollet sur la détermination des proportions dans lesquelles les corps se combinent d'après le nombre et la disposition respective des molécules dont les parties intégrantes sont composées'. Annales de Chimie (in French). 90 (1): 43–86.

- ^Scheidecker-Chevallier, Myriam (1997). 'L'hypothèse d'Avogadro (1811) et d'Ampère (1814): la distinction atome/molécule et la théorie de la combinaison chimique'. Revue d'Histoire des Sciences (in French). 50 (1/2): 159–194. doi:10.3406/rhs.1997.1277. JSTOR23633274.

- ^Clapeyron, Émile (1834). 'Mémoire sur la puissance motrice de la chaleur'. Journal de l'École Polytechnique (in French). XIV: 153–190.

- ^Loschmidt, J. (1865). 'Zur Grösse der Luftmoleküle'. Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften Wien. 52 (2): 395–413.English translation.

05th Apr 2019 @ 11 min read

Avogadro's law is also known as Avogadro's hypothesis or Avogadro's principle. The law dictates the relationship between the volume of a gas to the number of molecules the gas possesses. This law like Boyle's law, Charles's law, and Gay-Lussac's law is a specific case of the ideal gas law. This law is named after Italian scientist Amedeo Avogadro. He formulated this relationship in 1811. After conducting the experiments, Avogadro hypothesized that the equal volumes of gas contain the equal number of particles. The hypothesis also reconciled Dalton atomic theory. In 1814 French Physicist Andre-Marie Ampere published similar results. Hence, the law is also known as Avogadro-Ampere hypothesis.

Statement

For an ideal gas, equal volumes of the gas contain the equal number of molecules (or moles) at a constant temperature and pressure.

In other words, for an ideal gas, the volume is directly proportional to its amount (moles) at a constant temperature and pressure.

Explanation

As the law states: volume and the amount of gas (moles) are directly proportional to each other at constant volume and pressure. The statement can mathematically express as:

Replacing the proportionality,

where k is a constant of proportionality.

The above expression can be rearranged as:

The above expression is valid for constant pressure and temperature. From Avogadro's law, with an increase in the volume of a gas, the number of moles of the gas also increases and as the volume decreases, the number of moles also decreases.

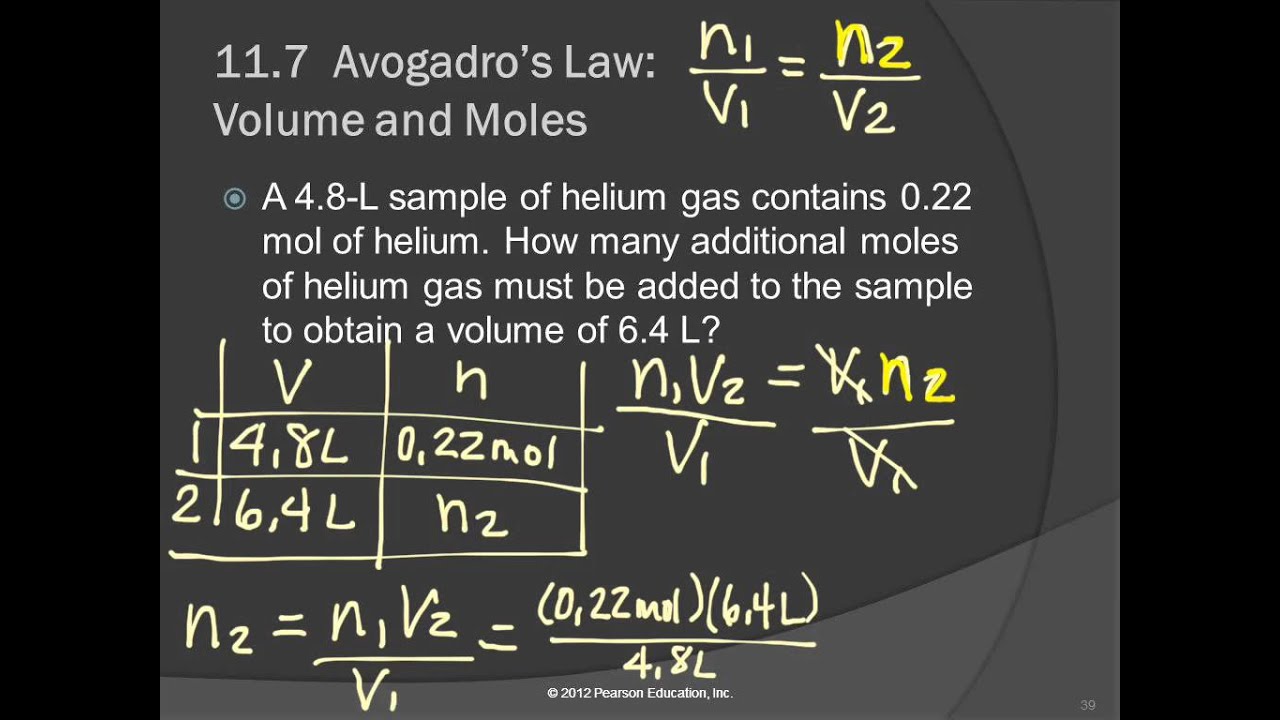

If V1, V2 and n1, n2 are the volumes and moles of a gas at condition 1 and condition 2 at constant temperature and pressure, then using Avogadro's law we can formulate the equation below.

Let the volume V2 at condition 2 be twice the volume V1 at condition 1.

Therefore, with doubling the volume, the number of moles also gets double.

The formation of water from hydrogen and oxygen is as follows:

$underset{1,text{mol}}{ce{H2O}}$}' alt='Water reaction'>In the above reaction, 1 mol, (nH2) of hydrogen gas reacts with a 1⁄2 mol (nO2) of oxygen gas to form 1 mol (nH2O) of water vapour. The consumption of hydrogen is twice the consumption of oxygen which is expressed below as:

Let say, 1 mol of hydrogen occupies volume VH2, a 1⁄2 mol of oxygen occupies VO2 and similarly for 1 mol of water vapour, volume VH2O. As we know from Avogadro's law, equal volumes contain equal moles. Hence, the relationship between the volumes is the same as among the moles as follows:

Avogadro's law along with Boyles' law, Charles's law and Gay-Lussac's forms ideal gas law.

Graphical Representation

The graphical representation of Avogadro's law is shown below.

The above graph is plotted at constant temperature and pressure. As we can observe from the graph that the volume and mole have a linear relationship with the line of a positive slope passing through the origin.

As shown in the above figure, the line is parallel to the x-axis. It means that the value of volume by mole is constant and is not influenced by any change in mole (or volume).

Both the above graphs are plotted at a constant temperature and pressure.

Avogadro's constant

The Avogadro's constant is a constant named after Avogadro, but Avogadro did not discover it. The Avogadro's constant is a very useful number; the number defines the number of particles constitutes in any material. It is denoted by NA and has dimension mol−1. Its approximate value is given below.

Molar Volume

Since Avogadro's law deals with the volume and moles of a gas, it is necessary to discuss the concept of molar volume. The molar volume as from the name itself is defined as volume per mole. It is denoted as Vm and having a unit of volume divided by a unit of mole (e.g. dm3 mol−1, m3 kmol−1, cm3 mol−1 etc). From the ideal gas law, at STP (T = 273.15 K, P = 101 325 Pa) the molar volume is calculated as:

Limitation of Avogadro's law

The limitation are as follows:

Avogadro's Law Calculator

- The law works perfectly only for ideal gases.

- The law is approximate for real gases at low pressure and/or high temperature.

- At low temperature and/or high pressure, the ratio of volume to mole is slightly more for real gases compare to ideal gases. This is because of the expansion of real gases due to intermolecular repulsion forces at high pressure.

- Lighter gas molecules like hydrogen, helium etc., obey Avogadro's law better in comparison to heavy molecules.

Real World Applications of Avogadro's Law

Avogadro's principle is easily observed in everyday life. Below are some of the mentioned.

Balloons

When you blow up a balloon, you are literally forcing the air from your mouth to inside the balloon. In other words, you are filling more moles of air in the balloon and it expands.

Tyres

Have you ever filled deflated tyres? If yes, then you are nothing but following Avogadro's law. When you pump air inside the deflated tyres at a gas station, the amount (moles) of gas inside the tyres is increased which increases the volume and the tyres are inflated.

Human lungs

When we inhale, air flows inside our lungs and they expand while when we exhale, the air flow from the lungs to surroundings and the lungs shrink.

Laboratory Experiment to prove Avogadro's law

Objective

To verify Avogadro's law by estimating the amount (moles) of different gases at a fixed volume, temperature and pressure.

Apparatus

The apparatus requires for this experiment is shown in the above diagram. It consists of a U-tube manometer (in the diagram closed-end manometer is used, but opened-end manometer can also be used) as depicted in the figure, mercury, a bulb, a vacuum pump, four to five cylinders of different gases and a thermometer. Connect the all apparatuses as shown in the figure.

Nomenclature

- V0 is the volume of the bulb, which is known (or determined) before the experiment.

- T is the temperature at which the experiment is performed, which can be determined from the thermometer (for simplicity take it as room temperature).

- P is the pressure at which the experiment is performed, which can be determined from the difference in heights of mercury level in the manometer.

- W0 is the empty weight of the bulb, and it is known (or determined) before the experiment.

- W is the filled weight of the bulb.

- Wg is the weight of the gas inside the bulb.

- M is the molar mass of the gas.

Procedures

- Take a gas cylinder attached it the bulb setup and also attached the pump to the bulb setup. Care must be taken while attaching the apparatus to prevent any leakages of the gas.

- First, close the knob of the gas cylinder and open the vacuum pump knob on the bulb. Evacuate the air filled in the system and by turning on the vacuum pump.

- Once the bulb is emptied, close the vacuum pump knob and switch off the vacuum pump.

- Start filling the bulb with the cylinder gas by opening the gas cylinder knob slowly until the desired difference in the mercury height is achieved. Note the height difference in the manometer. (The value of the height difference should be the same for all the readings.)

- Close all the knobs, also close the connection between the bulb and the manometer to isolate the gas inside the bulb. Disassemble the bulb from the manometer.

- Weigh the bulb on a weighing machine and note the reading down.

- This finishes the procedure for the first gas. Repeat the same procedure for different gases.

Calculation

Calculate the weight of gas (Wg) in the bulb by subtracting the weight of empty bulb (W0) from the weight of the filled bulb (W).

Avogadro's Gas Law

Then calculate the number of moles of the gas as:

The number of moles of all gases should be approximately equal within a small percentage of error. If this is true, then all the gases do obey the Avogadro's law.

If the experiment is performed at STP (T = 273.15 K, P = 101 325 Pa) , then we can also calculate the molar volume Vm as:

And its value should be close to 22.4 dm3 mol−1.

Examples

Example 1

Consider 20 mol of hydrogen gas at temperature 0 °C and pressure 1 atm having the volume of 44.8 dm3. Calculate the volume of 50 mol of nitrogen gas, at the same temperature and pressure?

As from Avogadro's law at constant temperature and pressure,

Therefore, the volume is 112 dm3.

Example 2

There is the addition of 2.5 L of helium gas in 5.0 L of helium balloon; the balloon expands such that pressure and temperature remain constant. Estimate the final moles of gas if the gas initially possesses 8.0 mol.

The final volume is the addition of the initial volume and the volume added.

From Avogadro's law,

The final number of moles in 7.5 L of the gas is 12 mol.

Example 3

3.0 L of hydrogen reacts with oxygen to produce water vapour. Calculate the volume of oxygen consumed during the reaction (assume Avogadro's law holds)?

For the consumption of every one mole of hydrogen gas, half a mole of oxygen is consumed.

As per Avogadro's law, the volume is directly proportional to moles, so we can rewrite the above equation as:

1.5 L of oxygen is consumed during the reaction.

Associated Articles

If you appreciate our work, consider supporting us on ❤️ patreonExample Of Avogadro's Law

.Avogadro's Law Explained

- 9

- cite

- response

Copy Article Cite

Example Of Avogadro's Law Problem With Solution